Come possono le istituzioni dell’economia sociale adattarsi per diventare più efficaci nel gestire l’incertezza della trasformazione dei sistemi complessi?

L’articolo approfondisce il tema delle meso-istituzioni, esaminando in particolare il caso di Consorzio Nazionale CGM come caso di innovazione sociale istituzionale, con lo scopo di analizzare tensioni ed opportunità di questo nuovo modello e di offrire interessanti spunti più ampi per l’innovazione istituzionale.

Abstract

How can institutions in the social economy adapt to become more effective in dealing with the uncertainty of system transformation?

This article focuses on “meso-institutions”, which we define as those that originated neither from a bottom-up (grassroots) approach nor from a top-down mandate (bureaucracy). In particular, it examines the case of CGM, a network of 600 social enterprises in Italy, to investigate how it is renewing its institutional configuration and mandate to better respond to both external and internal changes. CGM has the ambition to be a “reconfigurator” of multi-local systems that can establish new rules of the game in front of the main societal challenges. This entails adopting an innovative approach to define its strategy (from a classic “five-year plan” to a “compass”), reconfiguring its role (from a solution provider to a backbone organisation) and encouraging its members to embrace digitalisation, open innovation and a new business model (platform-based). The article will focus on the tensions and opportunities that this process is surfacing while pointing to broader lessons for institutional innovation.

1. Introduction

Environmental, social and technological transitions and related challenges (social justice, energy sustainability, the future of work, demographic ageing, etc.) call for a policy approach that questions the meaning of innovation as well as the roles of actors and institutions responsible for producing it [1]. The task is not to define new policy areas but to reformulate what constitutes a problem for society, both at the level of analysis of causes and identification of solutions. In particular, the ability to “see” social, economic, environmental and cultural issues from a different and interconnected perspective is critical. Therefore, a transformative approach to manage transitions requires new programming and execution capabilities, which, however, organisations are often not equipped with, given the prevalence of efficiency and compliance logics [2].

A possible answer to this need for organisational change, also of a cultural nature, can be sought by drawing insights from the governance of those diversified and ambivalent social processes that are represented by meso-institutions [3]. Transformative challenges, in fact, require enabling and facilitating a common intent, and they also necessitate the ability to collectively systematise and make sense of emerging phenomena and fragmented experiences. This requires knowing how to orchestrate resources and actors of various kinds to launch coordinated actions capable of elaborating socio-technical and political systems of a new nature, according to the principles of “integral development” [4].

Meso-institutions can play a critical role in this respect, as exemplified by the case of the Italian network CGM, which we will introduce in this paper. Organisations that operate at the micro level often appear unequipped with respect to broader, transformative objectives and, therefore, are unable to re-direct policies. At the same time, at the macro level, top-down attempts at rewriting a new social contract [5] struggle to build the legitimacy to bring about structural level change. Meso-level institutions, we argue, can be key drivers of transitions by bringing back the sense of aggregation, addressing and intermediation, often abandoned by some logics of collaborative economies [6]. The alternative is a dispersion in small experimental practices of rupture which remain atomised or, on the contrary, are incorporated and normalised by technocratic macro systems [7], thus nullifying the possibility of operating on a scale of transformation of systems.

In order to rise to this challenge, meso-institutions themselves need to change. They need to be rearticulated and managed to be more open, to be able to learn and to be endowed with capacity and power in order to trigger directionality on purpose, guide and govern long-term transformation processes, containing conflicts and solving problems of stability that the different parts of the systems (public organisations, third sector, for-profit companies, informal expressions of civil society) would otherwise have difficulty managing both in the sense of management and identification and exercise of their role. Meso-organisations could, therefore, be attributed to a new institutional role of leadership that Amin and Thrift call “institutional thickness” [8], or a capacity for interactive presence based not on procedural routines but on the ability to elaborate and reproduce socially shared cultures and values, thus activating focused and localised social innovations [9]. It is, therefore, not a mere organisational redesign but rather a launch of new institutional processes that relate to the micro–meso–macro levels [10].

After summarising the key research with respect to meso-level institutions, highlighting their contribution to the understanding of new models of social intermediation (Section 2.1), we will argue that the social economy and, in particular, the changing nature of social enterprises can play a leading role in the evolution of meso-institutions as actors of systemic innovation (Section 3). We will illustrate this through a case study of an Italian network of social enterprises—Consorzio nazionale CGM—which has been realized through the analysis of its previous strategic production and the main learnings from the support for the drafting and implementation of the most recent strategic plan (Section 4). CGM’s intent to reorient its strategy towards systemic transitions and its efforts to implement it through “open laboratories” with its key stakeholders exemplifies the new competencies needed by meso-institutions, specifically in the field of social economy, if they are to rise to the challenge of fostering socio-economic transitions (Section 5). We will end by offering (Section 6) some broader learnings on institutional innovation that can be inferred from the CGM experience, extending it to other similar initiatives, and calling for more research to further validate these insights.

2. Why Are Meso-Institutions Critical in Addressing Systemic Challenges?

The theorisation on meso-institutions can be recomposed within two main strands of scientific production. The first concerns studies that relate to different disciplinary fields—sociology, urban planning, law, political science—and those that recognise a focus of research in the “territory” [11]. This body of studies prevails an approach centred on the recognition of societal layers where conditions are created for the development of new institutions [12]. There is, therefore, a micro-social dimension infrastructured by daily interpersonal interactions, family groups and informal collective subjectivities. This is in contrast to the macro-social dimension that concerns large-scale social, political, economic and cultural phenomena (national, continental, planetary) generated and governed by institutions based on abstract norms, even if they are anything but neutral with respect to value options [13]. With respect to these polarities, the meso dimension is described and analysed as a “middle ground” between the micro-social life and the macro dimension, characterised by the presence of associative phenomena that, unlike the micro sphere, assume organisational forms but, in contrast with the macro sphere, intentionally maintain a rooting in social contexts. Expressions such as “intermediate bodies” highlight the peculiarities of institutions in the meso field, as they allow the achievement of economic, political and cultural goals through the coordination of the actions of many people and collective subjectivities, for example, on the division of labour or on value chains rooted in contexts that regenerate resources, not only strictly economic but also social and cultural [14]. The intermediary character of the meso-institutions consists of a function of representation that goes far beyond the lobbying approach with respect to specific interests, taking the form of a vision that is nourished by a plurality of economic, institutional and cultural exchanges. This capacity allows the meso dimension to reproduce important elements of common life: the establishment of personal and social identities, the definition of professional roles and the participatory patterns in societal dynamics [15].

The second strand of scientific production is a part of the institutional economy and considers the meso level the result of the progressive aggregation of complex processes and phenomena from which elements that present a certain degree of institutionalisation arise [16]. It is a “complex modelling” that goes beyond the micro-foundation of the macro, i.e., the institutional emergence from routine interactions, as well as overcomes the macro-foundation of the micro, which instead consists of the formation of individual behaviours within existing institutions. The peculiarity of the meso level regards the shift from an approach based on “mechanism” to a logic of “biology” that looks at organisational phenomena in terms of complexity rather than complication. Hodgson [17], in this sense, argues that structural emergence implies an “entity that has properties that could not be deduced from previous knowledge of the elements”. Other economists [18] have pointed out that the macro level has become less relevant in explaining the emergence of informal institutions and the related socialisation processes within them and, therefore, should be replaced by a meso conception enabling emergent properties. The meso level is, therefore, considered the most appropriate level of aggregation in order to produce and reproduce systems of institutions, especially looking at their cultural base. The institutions are considered here as an efficient way to solve coordination problems and, on this basis, generate new knowledge that is learnt jointly, often informally and tacitly. The neo-Schumpeterian approach [19,20] further deepens the sense-making character of the meso level when it highlights that a social rule cannot arise unless shared or “carried” by a heterogeneous group of agents.

2.1. The Theoretical Contribution of Meso-Institutions

The analytical described in the previous paragraph allows the two macro strands to converge around an evolution of society where failures and impatience with respect to organisations, often of large dimensions, designed as machines to achieve goals by maximising efficiency in the use of means, are becoming increasingly evident. Their raison d’être makes them great consumers of common resources (environmental and social), and their work generates increasingly evident negative externalities that cannot be compensated, also to avoid that merely compensatory solutions make them persist in their modus operandi [21]. In the face of an extractive rationality based on isolation from the context and an instrumental use of the environment that has now abundantly exceeded the limits of development, there is a need for a new “median” field of action within which organisations of various kinds are not considered only as tools but also as social processes capable of determining problem setting and problem solving according to procedural logics pertinent to the context. All this is to prepare policymakers for current and future challenges [12].

The analysis of the literature on meso-institutions, therefore, allows us to highlight, among others, an aspect of particular interest that can help to define a comprehensive theoretical framework, not referring exclusively to a particular type of organizational subjects that simply occupy a middle position between top-down institutions and bottom-up social processes.

Meso-institution models, in fact, highlight an intermediary function that is increasingly crucial for understanding the functioning of social systems and the challenges they face. The capacity, and the power, to mediate relationships is in fact the key function for interpreting phenomena of particular relevance such as the so-called “platformization” of increasingly large segments of the economy with its implications at the level of social behaviour and political choices [22]. From this point of view, intermediaries can take on very different characteristics, mainly determined by the orientation towards closure or openness of their intermediary function towards different actors who have different needs for meeting and exchange within markets, political arenas, social relations [23]. In summary, the exercise of the intermediary function is increasingly a key element in understanding the main societal processes—from value chains to models of political participation—in order to determine how effectively these are oriented towards sharing rather than extracting key resources of an economic nature, but also increasingly of a cultural and biopsychic nature [24]. Meso-institutions are increasingly called to compete with other models of intermediation, in particular with those of digital capitalism, in order to correct their increasingly evident distortions in terms of inequality and social control, developing new social “scaffolds” able to orchestrate different types of resources [25].

3. Social Economy: An Ecosystem for Changing Meso-Institutions

The “meso” dimension reconstructed from the conceptual theoretical point of view in the previous paragraph is configured not only as a residual intermediate space between a micro dimension that springs from interpersonal routines and a macro characterised by general and abstract rules. The meso level is rather configured as a context of action within which institutions capable of elaborating and reproducing elements of meaning and rules of functioning take shape. This can give a systemic approach to individual and collective action, enhancing its transformative impact [16], and this is a modality that the ancient Latins had well summarised in their famous motto “vitam instituere” [26].

At this point, it is important to understand which institutions populate the meso dimension, trying to highlight if they present peculiarities at the level of mission, methods of governance and management. These peculiarities should be noticeable, in particular, with regard to the institutions that make up the macro level—represented above all by public bodies and national and supranational corporations—and that play a dominant role within the social order. Compared to the micro level, it will instead be a matter of verifying how meso-institutions can act as an infrastructure for emerging social processes of an informal nature, constituting a value and organisational ontology that does not mortify them within a bureaucratic “iron cage” [27].

From this point of view, it may be interesting for cross theorisation and modelling related to meso-institutions to research strategy and policy production in the social economy. The reasons for analysing and fostering this convergence are different and promising. Studies in the meso field refer to “social economies” as a wide spectrum of organisations that enlarge the classic institutional taxonomy (particularly along the public–private continuum) and that are characterised by explicit objectives of innovation not only about product and process but broader economic, social and political systems [28]. The production of the field of social economy instead highlights some defining elements—prevalence of people over capital, carrying out activities of collective interest, openness of governance, limits to the concentration of wealth generated in terms of profits [29]—which could find a better realisation in “median” contexts. All these peculiarities are particularly visible on a territorial scale: the local dimension, in fact, allows to better combine organisational characteristics such as specialisation, autonomy and size containment of the different actors involved with the relational quality of the goods and services produced [30].

Of course, the social economy as a whole does not present these characteristics in a unique way and does not monopolise the meso dimension [31]. In this sector, in fact, there are entities such as cooperative enterprises and associations that can have a macro character or, on the contrary, a micro dimension at the limit of informality. On the other hand, and especially in recent times, there are other approaches and initiatives that cannot be included in the field of social economy in a strict sense—solidarity economy, care and governance of common goods, fundamental economy, etc.—but identify at the meso level, albeit in a not-always-linear way, their privileged field of action in order to elaborate and implement their transformative mission. In order to understand through which strategies it is possible to create and consolidate institutions that operate at the meso level, which can achieve systemic change, it may be useful to focus on a particular subject of the social economy, namely the social enterprise.

First of all, social enterprises have an explicit mission, also recognised by various regulatory frameworks [32], to pursue objectives of “general interest” in order to promote social cohesion through inclusive practices, particularly with respect to local communities and fragile people.

Secondly, social enterprises are also defined by the activities they carry out. These activities were identified, in the first phase, as niches within welfare (education, care, work inclusion), but in recent years, they have been associated with macro areas of action and related economies (tourism, agriculture, cultural production, environmental management, urban regeneration, etc.), in order to transform them into a more cohesive and inclusive model, thus increasing the social impact of these enterprises [33].

Thirdly, social enterprises, especially in some contexts like Italy, have reached a “critical mass” in quantitative terms and maturity of their cycle of life [34]. This evolution enables them to interact both in macro contexts—in particular in the definition of national and supranational regulations and development programmes—and in micro-linked dynamics, particularly the provision of services involving the beneficiaries, their primary networks and the local communities. To this end, social enterprises have structured over time a system of territorial networks on a meso scale—mainly provincial and regional—with functions of representation of interests and support to the members, but above all as localised and integrated agencies that try to bring social innovations of local development processes [35].

The evolution and progressive affirmation of the social enterprise within the social economy according to the characteristics and trends, allows us to propose more clearly the research question underlying this contribution. In fact, the social economy as a whole seems to be characterized not only as one of the contexts in which meso-institutions arise, but also as an ecosystem of resources that allows us to rethink the role of these institutions, in particular looking at their ability to exercise peculiar models of social intermediation capable of producing system changes.

4. Methodological Design to Investigate a Meso-Institution

To further deepen these evolutions and understand how it is possible to govern them, the strategic production—both in terms of content and approaches—has been identified as the main focus of analysis. In fact, strategic elaboration requires not only planning objectives and investing resources, but also identifying the main mechanisms and drivers of development that allow them to be achieved [36]. This last aspect appears crucial in the case of meso institutions as they are called upon not only to mobilise endogenous resources but to attract and orchestrate others of exogenous origin [18].

Deepening new approaches of strategic planning and reorganisation both internally and in relation with wider ecosystems, the case of the National CGM Consortium will be presented in the next paragraph. CGM is an important network of networks of social enterprises that in its almost-forty-year history has helped to define and put into practice the meso dimension. Today, CGM renews this challenge by trying to absorb important solicitations of change that come both from contexts that have contributed to infrastructure (local communities and the social welfare), and from macro and micro contexts that, in different forms and ways, appear increasingly interested in the meso-dimension of action.

The case study was carried out by reconstructing CGM’s strategic production, which has represented, since its foundation, a characteristic feature of its network organisational culture [37]. A further source of information arose from the re-elaboration of the main learnings related to the accompanying process, also carried out by the authors of this contribution, to the drafting of its new strategic plan for the consortium. While considering the risks deriving from an excessive proximity to the object of study, the benefits, typical of qualitative research approaches, of being able to collect “first-hand data” and their different facets in terms of meaning may also emerge [38]. A participatory approach that can help to describe and support emerging strategies of social intermediation which, although attributable to a highly specific initiative such as that of CGM, can still be transferred to other contexts, starting with that of the social economy.

5. CGM: A Leading Player of Meso-Institutions in the Italian Social Economy

The national consortium CGM was founded in the second half of the 1980s as a pioneering realisation of an institution-building process that contributed to the birth and development of social enterprise in Italy. This new form of enterprise can be considered an organisational hybrid resulting from the combination of subjects that characterised the Italian society of those years: voluntary associations, cooperative enterprises and, although not so explicitly, medium and small for-profit enterprises with value chains rooted at a territorial level [34]. The institutional innovation of social enterprise has particularly taken root in some fields, such as care, education, social-health welfare services and work integration of disadvantaged people, but also through some organisational methods linked, in particular, to the enlargement of governance models to a plurality of stakeholders [39] and to the construction and management of local networks (consortia). The mix between product innovation—through a new offer of goods and services of collective interest—and process—through open governance structures and innovation-oriented co-production networks—has represented an important accelerator for social entrepreneurship, promoting Italy as a leading country at the European level.

With respect to this general evolution, within CGM, there are also elements of discontinuity. In recent years, in fact, also within the CGM network, there have been phenomena of downsizing of territorial and community networks and growth of aggregation processes by merger and incorporation, which has led to an increase of the organisation’s size, considering, in particular, the number of workers and the economic turnover [40]. At the same time, the use of non-cooperative social enterprise vehicles has increased, often to support technology—and capital—intensive investments [37].

The experience of CGM can be considered emblematic because its configuration as a meso-institution capable of aggregating, from a systemic perspective, a plurality of social enterprises takes place mainly through a strategic approach. Looking at the strategic production of CGM and, particularly, the most recent elaboration can allow to understand how this network has managed its meso-institution character over time, obtaining useful learnings not only in terms of internal policy but also on a wider spectrum of entrepreneurship and social economy initiatives that in recent times have expanded and diversified. The meso dimension, particularly, can allow to better focus the theme of scalability in the social sphere, overcoming a polarised debate [41]. On the one hand, there are proposals based on the adoption of scaling models developed in different contexts, mainly those of technological innovation, which often adopt a macro logic. On the other hand, there are solutions that instead emphasise elements of rootedness and localism with the aim to protect micro initiatives with respect to vertical integration approaches which risk confining social innovation into a niche [36].

The most recent strategic plan of CGM [42] appears, from this point of view, innovative not only with respect to the contents but also with regard to the methods of elaboration. In particular, the new plan tries to overcome an approach based on the definition of a list of “flagship projects” that can be aggregated within work areas and organisational functions (R&D, training, fundraising). There are, in fact, many areas of action within the purposes of “general interest” that define the mission of the social enterprise (from those related to care to non-care ones), and, therefore, planning could not concern a mere coordination of work areas or a simple list of the needs of the CGM’s members.

For the new leadership of CGM, a change of approach was necessary that identified in a strategic vision based on “drivers of purpose” on which to plan and invest rather than a rigid scheme based on a means–end rationality. These directions cross the plurality of signals arising from the contact points and connections of the CGM network. This new strategic approach made it possible to design and manage some new “open laboratories” to work with some champions of the network in order to model projects, programmes and strategies and circulate them in the network as common learning in terms of knowledge, culture and values. The expectation of the new board of CGM is that the initiatives and projects that emerge from the network can take a more evident systemic connotation, with the effect of re-vitalisation of the system itself.

5.1. From Static Strategy to a “Compass” for Institutional Innovation

The constituent element of the most widespread planning processes within contemporary organisations is “predetermination”, which imposes a narrow vision of what the relevant signals are and weakens the ability to use skills and resources in a contingent and modular way [43]. These approaches are based on a reiteration of patterns unable to adapt to ever-changing contexts and repeated crises that characterise our time. The major challenges—climate and environmental, societal, territorial, geopolitical and economic—have long required us to rethink both the approach and the method of strategic planning. Public and private organisations are increasingly displaced by combining new challenges with planning methods that appear ineffective because they are based on closed sectors and organisations and on defensive and non-designed networks. In summary, an approach to planning focused on control, stability, uniformity and efficiency and based on an organisational modelling that provides for the increase of rules, procedures and hierarchy seems to be not dysfunctional in some aspects, but structurally inadequate. It is, therefore, necessary to work on tools and methods to manage uncertainty, thinking of planning not as a linear process but as a continuous restructuring hinged on strategic directions and a vision of the future [44].

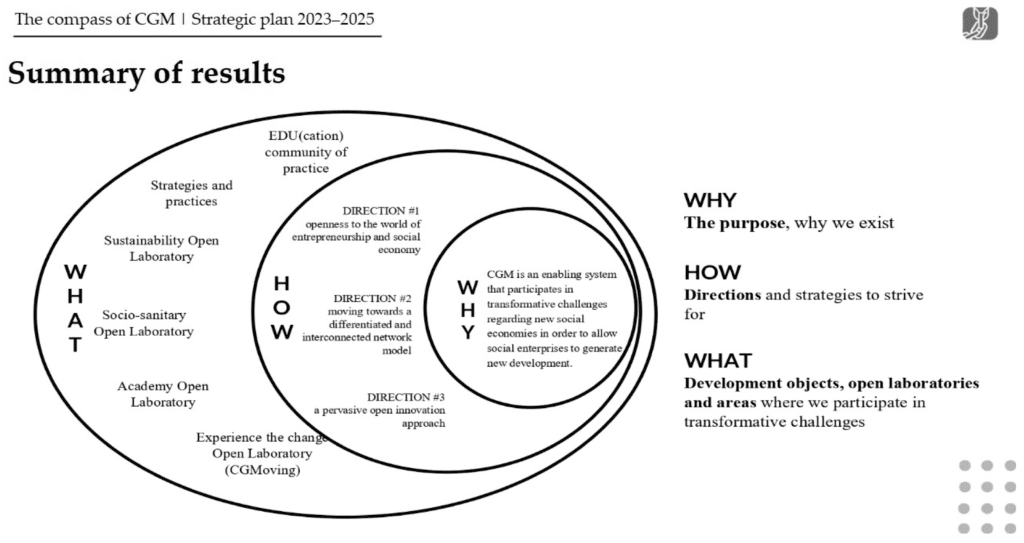

All these transformations have required CGM to reconfigure itself as a meso-institution through a new way of strategising. The new strategic plan appears to be in discontinuity with regard to the methodological and mindset aspect, trying to interpret the needs of its network and to amplify its impact in a rapidly changing context. The plan is, therefore, a compass built on principles and directions to drive its system to evolve, to “stay into challenges” and to anticipate repeated crises through a new approach to design an organisational and strategic management [45]. The result of this new approach is summarised in the next Figure 1 and consists of the definition of a “statement of purpose” about the role of CGM in the near future, the identification of some “drivers” that follow, in a proactive way, the grand challenges and a series of “open laboratories” to experiment with this new strategic posture of the consortium.

The new strategy was built in a more participatory way following a process of gradual involvement of the board of directors and staff who built and validated the strategic directions, as well as the new role of the network as a development agency. Following the elaboration of the plan, the strategic companies of the consortium focused on some key areas, such as work, finance and digitalisation, which were able to decline the strategic directions in a series of joint actions. Finally, the plan was completed and, at the same time, implemented through the network of social enterprises and their local consortia, thanks to the participation in some strategic open laboratories.

The plan-compass is, therefore, configured as a process of capacity building for the entire organisation. The open laboratories, in particular, are set up as a sort of “gym” for enterprises considered more ready and equipped with the aim of observing how developmental projects arise from transformative challenges, therefore becoming cross-areas. The challenge of laboratories is to overcome a siloed design approach, approaching transitions as incubators of transformative projects for the systems they are referring to and thus deciding which economies they produce, through which alliances, etc.

5.2. Implementation of the Compass: The Case of Digital Transformation

Among the various open laboratories, one appears emblematic for representing the effects of the new strategic approach. The laboratory concerns the digital transformation of welfare through the adoption of platform logics and models [46]. In its realisation, the laboratory highlights some elements of “added value” with respect to CGM as a meso-institution and its way of achieving this structure through different methods of planning and strategic action.

First of all, these open laboratories clarify the reference to mainstream transformative challenges, such as digital transformation, with respect to which it had so far taken an execution approach, if not, in some cases, of idiosyncrasy, representing itself in some way “sheltered” from its effects. This change of approach has helped to unlock an innovation potential that has taken shape in the launch of a startup (CgMoving) dedicated to the construction of welfare platforms and, more generally, to accompany change management processes deriving from conscious and intentional processes of digital transformation of the companies in its network [47].

Secondly, the laboratory has allowed not only to create and systematise product innovations but to rethink in a comprehensive way the “core” dimension of CGM as a meso-institution, namely the construction and maintenance of networks on a local scale with co-production value chains. In this sense, the activities of the open laboratory have made it possible to approach the digital dimension not only in terms of management efficiency but above all in terms of transformative impact. For example,

- a data-driven approach compared to a classic focus of social enterprise action, namely the “reading of needs”, not referring only to specific targets but generating an overall vision that allows to design real systemic actions;

- a better ability to structure ideas with transformative value, adopting a pervasive approach of open social innovation [48] that allows cross-sector work, enriching co-production chains with an authentically “shared value”, through the involvement of other suppliers and partners not necessarily coming from the field of social enterprise in a strict sense;

- a more evident game-changer posture in decision-making and programming processes with public administrations and other players (e.g., foundations, social investors) within which, especially in recent years, social enterprises have taken a passive rather than transformative orientation.

The digital laboratory, in summary, confirms that the new planning method seems to have introduced a “curvature” in the strategic action of CGM, re-enabling this meso-institution to work on the structural conditions to affect various areas: local governance, finance and planning–programming tools, participation, etc. This has happened, in particular, through the use of technological and social platform infrastructures that have facilitated the formation of new supply systems, but also through new purpose alliances, based on intentional, positive and durable impacts rather than on the mere coordination of existing resources [49].

6. Conclusions: Learnings about the Process of Institutional Innovation

In this paper, we have argued that meso-institutions provide a particularly fruitful observatory to analyse the dynamics of institutional innovation in the face of systemic challenges and a heightened level of uncertainty. This is because, on the one hand, they can play a useful coordinating, layering role that overcomes the limitations and fragmentation of many micro-level interventions. On the other hand, their fluid and adaptive role, when embraced, furnishes them with the flexibility and space to manoeuvre that is often missing in macro-level institutions and is necessary for deep, systemic transformations [50]. We argued that the social economy, because of its dynamics and trajectory, is a sector where the adaptation challenge of meso-institutions is particularly evident.

To better understand the dynamics of institutional redesign in this sector, we introduced the case of the Italian network CGM, an organisation that has embraced the need for renewal to maintain its relevance and help its members better address systemic challenges. CGM represents a case study in many respects emblematic of the way in which the social economy declines the role of meso-institution: widespread use of multi-level networks, governance structures open to a multiplicity of stakeholders, innovation not only of product and process but also of an institutional nature and, last but not least, emphasis on the strategic dimension of development, referring to wider supply chains and territorial contexts. We have shown that embracing a system transformation perspective entails a fairly profound process of questioning institutional roles, practices and processes, whether it is strategy setting and implementation, delivery of services, all the way to exploring new opportunity areas such as digitalisation. Institutional innovation, therefore, is a matter of deliberate, strategic design. It requires building organisational will to question one’s identity and, in the case of meso-institutions, this is by definition a process that has to be co-owned with a number of different constituencies whose readiness for change and embracing a new north star might vary.

The case of CGM illustrates how the institutional innovation challenge for meso-institutions requires acquiring new dynamic capabilities, which can also be the subject of capacitation programmes for other actors with similar characteristics, in particular,

- The capacity to embrace long-term thinking so that dynamics of system transformation can take their course (while at the same time, delivering immediate short-term benefits to key constituencies).

- The capacity to build new organisational infrastructure, particularly, (i) a mission-oriented approach that allows coherence of intent while allowing for local-level adaptation; (ii) flexible networks that take different forms and shapes but are united by a transformational intent; (iii) projects and programmes that cut across traditional silos and allocations of tasks and budgets; in some cases, this might take the radical form of questioning the projectized logic of much of the social economy work in itself; (iv) governance mechanisms which enable managing the uncertainty and unpredictability that ensue from abandoning well-established cooperation mechanisms to embrace the above-mentioned changes [51].

- The capacity to embed the transformational logic not only in programmatic work but also in back-office operations (e.g., procurement, human resources) operating like a “backbone organization” [52].

Even though CGM is arguably one of the most significant meso-institutions in the social economy in Italy, this and others’ learning elements can be transferred to a wider territorial and sectorial range, thus outlining a new frontier of systemic innovation, thanks also to policy tools such as the “Social Economy Action Plan” adopted by the European Commission [29]. Further research is needed to establish whether similar institutional innovation dynamics are present in other comparable institutions both in Italy and in other parts of the world so that more general conclusions can be drawn about the challenges of re-design for system transformation.

Author Contributions

All authors participated in equal manner in the research and the definition of the article, yet Section 1 and Section 5 were written by G.Q., Section 2 by F.B., Section 3 by F.Z., Section 4 by F.B. and F.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

- Sendra, P.; Sennett, R. Designing Disorder: Experiments and Disruption in the City; Verso: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gerli, F.; Calderini, M.; Chiodo, V. An ecosistemic model for the technological development of social entrepreneurship: Exploring clusters of social innovation. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2022, 30, 1962–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ménard, C. Meso-institutions: The variety of regulatory arrangements in the water sector. Util. Policy 2017, 49, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rago, S.; Venturi, P. Co-Operare. Proposte per Uno Sviluppo Umano Integrale; Aiccon: Forlì, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shafik, M. What We Owe Each Other: A New Social Contract; Vintage Publishing: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pais, I.; Stark, D. Algorithmic Management in the Platform Economy. Sociologica 2020, 14, 47–72. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, M. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Zero Books: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Coenen, L.; Hansen, T.; Rekers, J.V. Innovation Policy for Grand Challenges. An Economic Geography Perspective. Geogr. Compass 2015, 9, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, F.; MacCallum, D. Advanced Introduction to Social Innovation; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- March, J.G.; Olsen, J.P. Rediscovering Institutions; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Magnaghi, A. Il Principio Territoriale; Bollati Boringhieri: Turin, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Donolo, C. L’Intelligenza delle Istituzioni; Feltrinelli: Milan, Italy, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pistor, K. The Code of Capital: How the Law Creates Wealth and Inequality; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Becattini, G. La Coscienza dei Luoghi. Il Territorio Come Soggetto Corale; Donzelli Editore: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barbera, F.; Jones, I.R. (Eds.) The Foundational Economy and Citizenship: Comparative Perspectives on Civil Repair; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Elsner, W. Why Meso? On Aggregation and Emergence, and Why and How the Meso Level is Essential in Social Economics. Forum Soc. Econ. 2007, 36, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, G.M. From micro to macro: The concept of emergence and the role of institutions. In Institutions and the Role of the State; Burlamaqui, L., Castro, A.C., Ha-Joon Chang, H.-J., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 103–126. [Google Scholar]

- Elsner, W.; Heinrich, T. A simple theory of ‘meso’. On the co-evolution of institutions and platform size—With an application to varieties of capitalism and ‘medium-sized countries’. J. Socio-Econ. 2009, 38, 843–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopfer, K.; Foster, J.; Potts, J. Micro-meso-macro. J. Evol. Econ. 2004, 14, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J. From simplistc to complex systems in economics. Camb. J. Econ. 2005, 29, 873–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, M. Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, P.; Leyshon, A. Platform capitalism: The intermediaton and capitalisation of digital economic circulation. Financ. Soc. 2016, 3, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudici, A.; ReinMoeller, P.; Ravasi, D. Open-system Orchestration as a Relational Source of Sensis Capabilities: Evidence from a Venture Association. Acad. Manag. J. 2018, 61, 1369–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehdonvirta, V. Cloud Empires: How Digital Platforms Are Overtaking the State How We Can Regain Control; Mit Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nambisan, S.; Sawhney, M. Orchestration Processes in Network-Centric Innovation: Evidence from the Field. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2011, 25, 40–57. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, R. Vitam Instituere. Genealogia dell’Istituzione; Einaudi: Turin, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institution Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wijk, J.; Zietsma, C.; Dorado, S.; de Bakker, F.G.A.; Martì, I. Social Innovation: Integrating Micro, Meso and Macro Level Insights from Institutional Theory. Bus. Soc. 2019, 58, 887–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Building an Economy That Works for People: An Action Plan for the Social Economy; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Borzaga, C.; Calzaroni, M.; Fontanari, E.; Lori, M. (Eds.) L’Economia Sociale in Italia. Dimensioni, Caratteristiche e Settori Chiave; Rapporto di ricerca Istat Euricse; Istat: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Roelants, B. Worker Co-operatives and Socio-economic Development: The Role of Meso-level Institutions. Econ. Anal. 2010, 3, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fici, A.; Rossi, E.; Sepio, G.; Venturi, P. Dalla Parte del Terzo Settore. La Riforma Letta dai Suoi Protagonisti; Laterza: Bari-Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. European Union Social Enterprises and Their Ecosystems in Europe; Comparative Synthesis Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Borzaga, C.; Musella, M. (Eds.) L’Impresa Sociale in Italia. IV Rapporto Iris Network. Identità, Ruoli e Resilienza; Iris Network: Trento, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tricarico, L.; De Vidovich, L.; Billi, A. Entrepreneurship, inclusion or co-production? An attempt to assess territorial elements in social innovation literature. Cities 2022, 130, 103986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzberg, H. The strategy concept I: Five Ps for strategy. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1987, 30, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturi, P.; Zandonai, F. (Eds.) Ibridi Organizzativi. L’Innovazione Sociale Generata dal Gruppo Cooperativo CGM; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Borzaga, C.; Sacchetti, S. Why Social Enterprises are Asking to be Multi-Stakeholder and Deliberative: An Explanation Around the Cost of Exclusion; Euricse Working Papers 75/15; Euricse: Trento, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istat. Struttura e profili del settore nonprofit. Anno 2020; Istat: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Seelos, C.; Mair, J. Innovation and Scaling for Impact: How Effective Social Enterprise Do It; Stanford Business Book: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Consorzio Nazionale CGM. CGM in Trasformazione: Una Bussola per Orientare Scopo, Direzioni e Funzioni; Piano di Sviluppo; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K. Making Sense of the Organization; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, N.; Hazeldine, S.; Quaggiotto, G. Two Paths to Supporting Grassroots Innovation. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 18 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cattapan, N.; Battistoni, F. Dalle transizioni alle sfide per l’innovazione trasformativa. che-Fare, 2 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Arcidiacono, D.L.; Pais, I.; Zandonai, F. Plat-Firming Welfare: Examining Digital Tranformation in Local Care Services. In Digital Platforms and Algorithmic Subjectivities; Armano, E., Briziarielli, M., Risi, E., Eds.; University of Westminster Press: London, UK, 2022; pp. 203–214. [Google Scholar]

- Tombari, M. (Ed.) Pubblico, Territoriale, Aziendale. Il Welfare del Gruppo Cooperativo CGM; Esté: Milan, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mair, J.; Gegenhuber, T. Open Social Innovation. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2021, 19, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Busacca, M.; Zandonai, F. Platform social enterprises as a new model for co-production. Studi Organ. 2020, 1, 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begovic, M.; Quaggiotto, G. Pivoting to strategic innovation: 3 Things we learned along the way. Medium—UNDP Strategic Innovation, 16 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, W.F. Transformative Innovation and Socio-Technical Transitions to Address Grand Challenges; Working Paper; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, S.; Merchant, K.; Kania, J.; Martin, E. Understanding the Value of Backbone Organizations in Collective Impact: Part 2. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 18 July 2012. [Google Scholar]

A cura di: Francesca Battistoni, Giulio Quaggiotto e Flaviano Zandonai

Pubblicato su: Sustainability